What Makes Someone Count?

Surviving the institution of incarceration

“Kentucky” has been in and out of prison for the last twenty years. Mostly in. He called me for the first time on his birthday, July 26, 2020. That night, I made him a poster and put it up on the wall facing the prison, right outside his window. He called me every day after that for months, until I told him I needed a little space. Then it was every other day. I check in on his grandma, Minnie, from time to time to make sure she’s okay. She’s the only relative who still seems to care about Kentucky’s well-being. Brothers, cousins, uncles, and friends have dropped off over the years, or have enough of their own problems to deal with. His mother passed away while he was locked up. He calls me his little sis. He signs his letters, “big bro.” I can’t explain our connection. There’s no reason we should be friends, or pseudo-siblings. We have very little in common. His Kentucky accent is thick and I tease him by imitating the recording that plays of him saying his name every time he calls. He loves to hear me say it, not just because it’s entertaining, but because it’s a tiny reminder that he’s a person, with a name. Because the rest of the time, he’s a number, a nobody

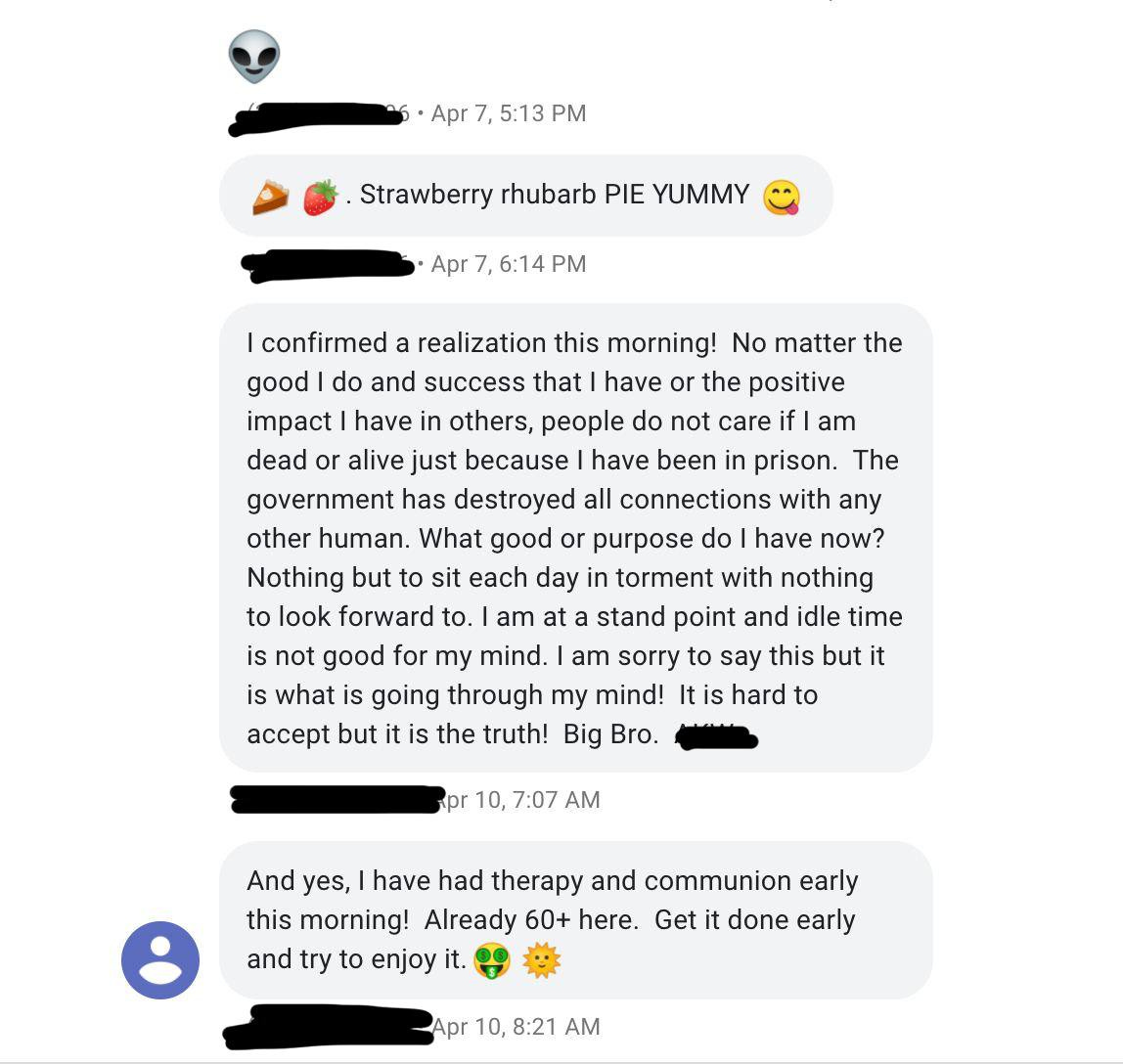

.Kentucky was released at the beginning of this year after doing an 18-month bid for violating his parole. We continued to speak or text almost every day. He loved discovering new emojis and sent me photos of his new room when he finally left the halfway house. He financed a beamer and washed it every day. He called his car cleaning ritual his “therapy.” He was going out on job interviews consistently. One company wouldn’t hire him because he was over-qualified. They would have had to pay him more due to his education and training. Some days were better than others. He had no friends and didn’t feel any sort of kinship with the men in similar positions. Good days involved finding a pair of “Lucky” jeans at Goodwill or watching Kentucky win a basketball game. Bad days involved him thinking of ways to send himself back to prison. I begged him to call me anytime he had those thoughts. He did. But the subconscious works in mysterious ways.

One day I got the call I dreaded. I hadn’t heard from him for a few days. Then, I received a collect call from the county jail. His accent wasn’t as pronounced this time. He sounded weak, broken. I have yet to learn the whole story, but he’s been in the county jail for over three months now, awaiting his fate. He has been refused medical attention despite having a serious illness. Sometimes he gets painkillers, sometimes not. I can only imagine it’s some version of hell in there, but he persists. It’s a familiar hell for him. With nothing much else to do, he started writing me letters. He says he hasn’t written this much in his entire life. I can tell when his hand gets tired, his cursive turns into a code I need to decipher. Each envelope contains about five or six pages, single-spaced, back to back. A man’s life. Unknown to anyone else in the world, maybe even himself, until it flows through his pen. The life he had, the life he imagined, the pain he’s endured, the hope he’s lost. He’s a product of a society and a system that’s failed him. He’s made mistakes, sure, but he’s more than paid for them. After serving his time, with no support, no context for his experiences, and no tools, he’s supposed to “re-integrate” into society. Sometimes I wonder if I could have done more, other times I know I’ve done more than anyone ever in his life. But I hope that can change. I hope more people can find it in their hearts to care about their fellow humans, whether they’ve made mistakes and paid for them with prison time or not.

If you would like to donate money to support people in prison, please send to the Forgotten Ones CashApp. It will be used to order books or send basic commissary to those in need.